Community Rails for Livelihoods | From The Margins #4 - 12th June, 2025

Rebuilding India’s Last Mile Distribution Networks

On a congested Bangalore Monday, I spotted Ajit at a pay-and-park lot (run by a service provider - Minerva) near the airport. Raised in Mulbagal, a small town in Kolar district of Karnataka, he moved to the city for its ride-hailing boom. One by one he persuaded cousins, school friends and even his old neighbour’s son to follow. “First thing I show them isn’t the apps,” he said, pointing around the lot. “It’s Minerva.” A compound that doubles as a starter kit for migrant drivers—dorm beds, cheap meals and hot-water showers. Drivers call him “Ajit Anna”, the elder brother; soaking up his advice on best airport queue timings, fuel saver discounts and earnings optimisation. He wasn’t assigned the role; he grew into it, turning his own hustle into a roadmap that every newcomer could follow.

Journeying east to Chennai’s Oragadam industrial hub - I met Prakash, a former migrant who now recruits young workers from Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh for big factories like Royal Enfield, JBM, and Britannia. He arranges their travel, finds them shared rooms, handles their job cards, signs them up for government benefits, and coaches them on saving and sending money home—acting less like a contractor and more like a full-time lifeline for the seven-in-ten factory workers who arrive from far-off villages.

These experiences sparked a vision. Imagine this: Ajit, the street-wise driver-mentor in Bengaluru’s ride-hailing community, and Prakash, the tireless job-broker on Chennai’s factory belt, become more than isolated change-makers. They’re armed with an AI sidekick and a marketplace of plug-and-play services—micro-loans for equipment, pay-per-use health cover, zero-fee remittances—each one precision-built for specific livelihoods. With their help, the platform curates the catalog, handles the tech, and every time a worker signs up for a livelihood boost, they benefit as well. The bigger the impact, higher their earnings—turning local heroes into self-sustaining engines of community prosperity.

The Last-Mile Distribution Gap

About 1 billion Indians—roughly 70 % of the population—live in “Aspirer” and “Seeker” households earning ₹ 1.25–15 lakh a year. These ≈ 237 million households are spread across thousands of villages, towns, and cities. Hence, serving them is hard: a rural bank branch can cost ₹1.5 - 2.5 lakh a month and an ATM ₹ 75–80 k1. Even the 1.35 million rural and 0.36 million urban business correspondents (BCs)2, empowered to conduct basic banking on the banks’ behalf, are far from effective. Fintech BCs like Spice Money (1.1 million agents3) and PayNearby (5 million agents4) are solving for some of these inefficiencies; but they largely remain rural-focused.

The last mile distribution gap is more pronounced in Urban Bharat. Nearly 29 % of Indians relocate within a decade5 and urban India is on track to hit 630 million6 people by 2030. In these cities about 80% of jobs are informal7 , leaving millions of migrants especially vulnerable to missing identity documents, income shocks, digital fraud and exclusion from formal finance. Urban BCs are financially unviable (earning ₹ 7–15 k8 a month after investing in devices), battle structural distribution constraints and compete with digital apps & ATMs; so banks see little profit in scaling them.

Evolution of Last-Mile Distribution Models

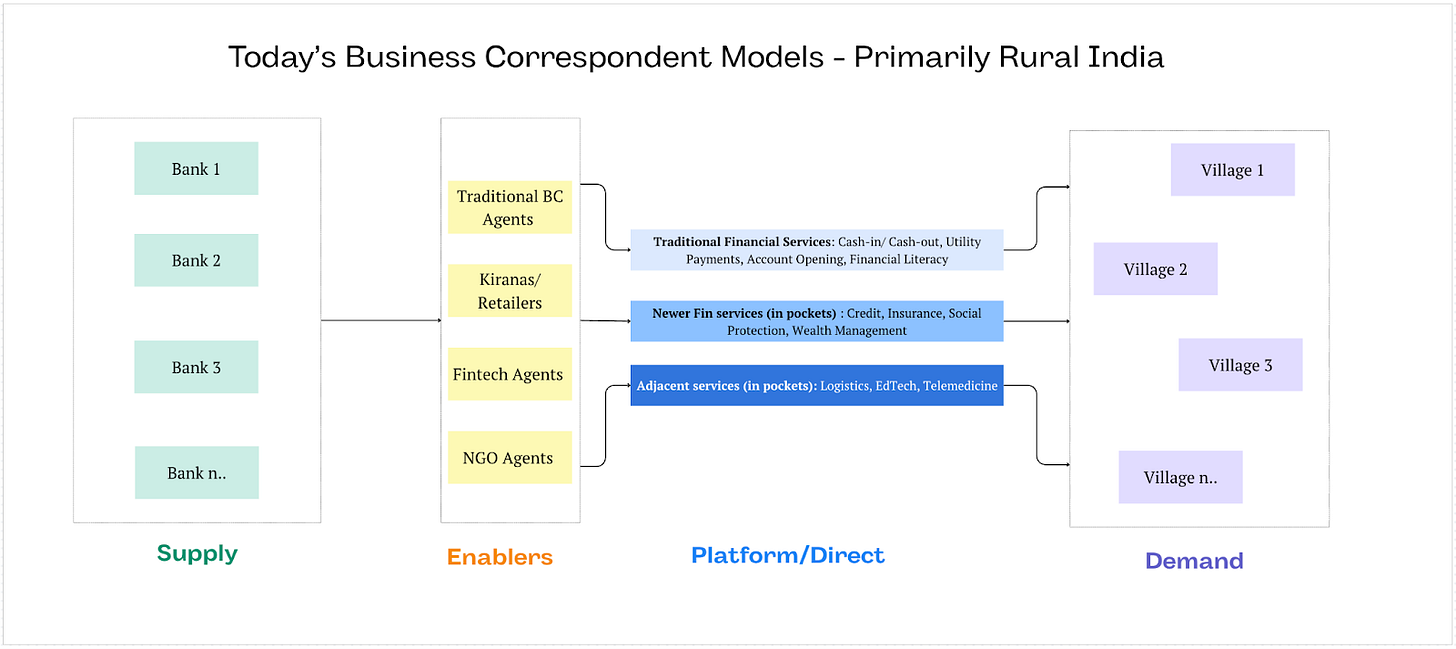

Traditional Business Correspondent (BC) Networks to Tech-enabled ‘Phygital’ Platforms

India’s “branchless banking” journey began in the 2000s when the RBI rolled out the Business Correspondent (BC) model—local agents using micro-ATMs and Aadhar Enabled Payment System (AePS) to let customers check balances, withdraw cash and receive government payments. The model exploded after the 2014 Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana: tens of millions of Jan Dhan accounts9 were opened and, during the pandemic, BC outlets paid out COVID-19 relief through Direct Benefit Transfers10 almost overnight. Early networks run by banks, specialised intermediaries like FINO, Eko, Vakrangee and a few NGOs, proved the concept but struggled with thin commissions, high field costs and patchy uptime.

The next wave followed as tech firms such as Spice Money, PayNearby and Roinet armed ‘kirana’ owners and small entrepreneurs with smartphone apps. A single “Digital Pradhan” or “Adhikari” (in Spice Money’s terminology) could now handle AePS cash-in/out, domestic remittances, utility bills, insurance, loan sourcing and even assisted e-commerce—turning the corner shop into a mini-service hub. GroMo (2019), the newest entrant to the distribution business, lets any individual, not just shopkeepers, sell ~160-plus products on behalf of leading banks and fintechs; rapidly growing to 3.6 million partners across 19,000 PIN codes.11

Urban Bharat is still in search of a Last-Mile Network

Urban low-income families depend on a patchwork of programmes and local groups rather than a true last-mile network. The government’s PM-SVANidhi provides access to micro-loans for street vendors while its Self Help Groups formed under Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NULM) help with skills training. Construction-worker welfare boards pay insurance and pensions. A handful of public-sector, small-finance and payment banks maintain BC presence in slums, while community collectives such as Kudumbashree12 educate residents and connect them with banking services.

Fintech efforts remain niche. Start-ups such as Dvara Money, Bandhu, Chalo Network, FatakPay and Vitto13 focus on urban underserved (including migrants), offering savings accounts, gold savings, documentation help, employer-facilitated credit or AI-scored micro-loans and operate at modest scale.

Big digital gig platforms could in theory be ideal distributors—Ola, Uber, Swiggy and others reach hundreds of thousands of workers—yet surveys show a gap: every driver or rider is app-savvy14, but fewer than half ever bought a financial product in-app15. Further, some of these players link products like insurance to performance on the job16 thereby alienating many. Workers cite hidden deductions, confusing terms and fear of losing already volatile income17, underscoring why urban India still lacks a trusted, large-scale channel for tailored financial & non-financial products.

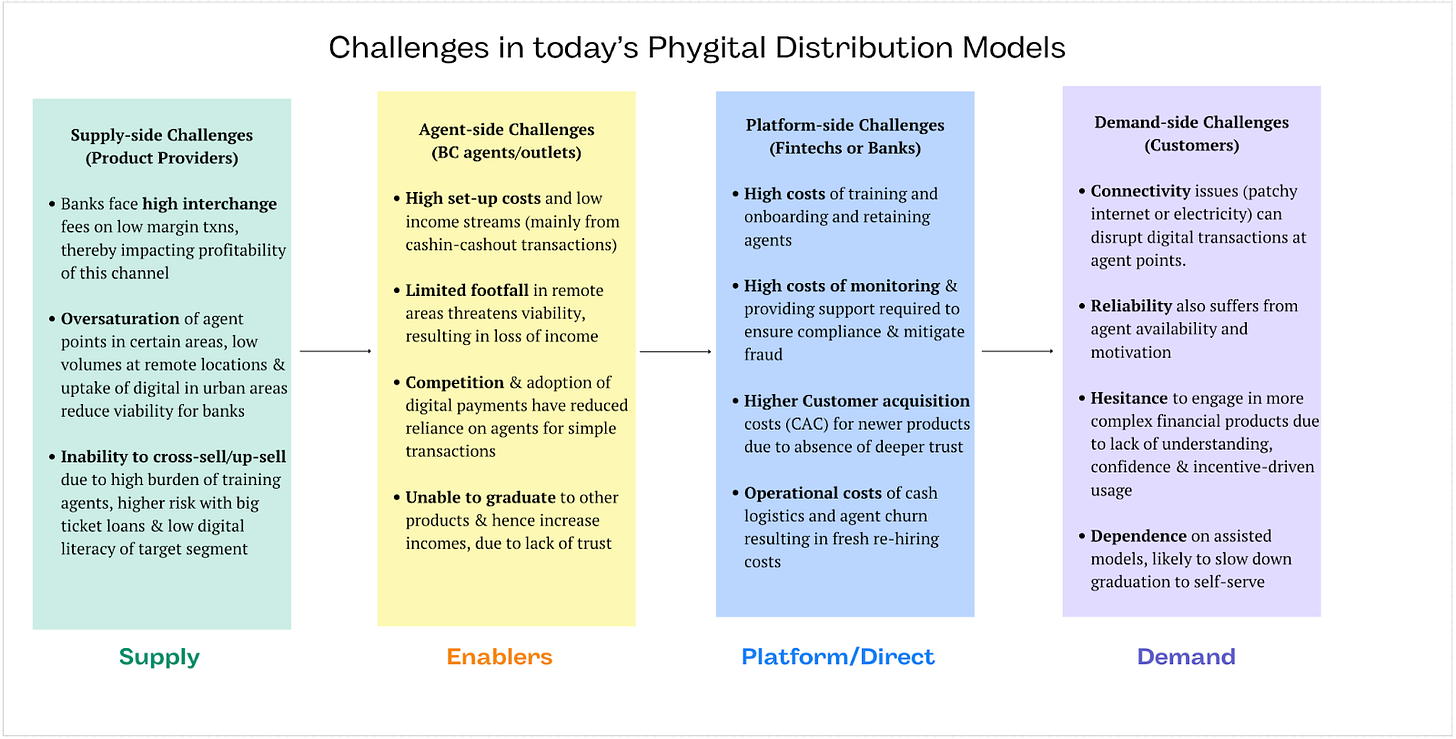

Challenges of today’s Phygital Last-Mile Model

The phygital model of financial distribution – combining physical touchpoints with digital platforms – has been pivotal in extending banking to underserved communities, especially in rural India. It comprises several ecosystem actors: (1) Banks/NBFCs on the Supply Side (2) BCs/BC entities (3) The platform (apps & devices) used by Fintechs like PayNearby (4) Rural residents on the Demand Side

Despite its successes, and the fact that it is mostly absent in Urban Bharat - the phygital model faces significant drawbacks and challenges across all players in the ecosystem.

The Case for a Community Livelihood Exchange

In the rural context, distribution of financial services is still scattered, but in pockets, is formalised either by existence of deeply entrenched BC networks or via Farmer Producer Organisations/Co-operatives as we described in posts 1 and 3. These collectives also make available non-financial services like crop advisory and access to better farming inputs, thereby uplifting the entire value chain. However, no such formalisation or value chain enhancement exists in the context of urban informal livelihoods like manufacturing, gig work or construction work.

Urban India’s “underserved” middle spanning ~90 million households earning ₹ 1.25-15 lakh household income per annum are distributed across livelihoods18 that are highly informal, possess limited income enhancement opportunities and are cut off from access to formal finance.

My thesis revolves around a new model for last-mile distribution, focused on urban underserved (with a potential to extend to rural areas) that is livelihood-focused, highly tailored and community-centric.

“Livelihood-focussed” means it brings together micro-communities involved in the same or similar occupations or livelihoods

“Products/ services tailored to Livelihoods” guarantee inherent usage, as they’d be critical to improving incomes

“Community Centric” via Community Champions who are more deeply entrenched and invested in the communities than BCs. They’re AI assisted and better incentivised.

Thus, Ajit for example, alongside dispensing invaluable advice on gig work, can get a group of drivers to (1) access affordable vehicle loans (2) avail fuel & maintenance discounts (3) get instant access to govt. benefits (4) connect to cheap housing options (5) access comprehensive health/accident cover, etc.

Similarly Prakash can onboard workers onto a platform where he can facilitate (1) access to zero-balance bank accounts (2) affordable group housing (3) small ticket loans (4) micro-insurance (5) early wage advances etc.

Pillars of the Exchange

The three-sided marketplace structure of the exchange, connecting demand, supply, and community champions forms a virtuous flywheel. Highly relevant livelihood products offered by trusted members of the community, will drive higher demand for and usage of these products -> resulting in higher margins for community champions & suppliers -> driving more providers/suppliers to sign up to the platform -> and hence in-turn further increasing demand.

What differentiates this model from all other existing last-mile networks are these three structural features:

I. Users and Products are organised by Livelihoods

Livelihoods bind people together, especially in urban migrant contexts where fragmentation is high & sense of community is low. They have similar needs and aspirations; hence enabling us to deeply understand each community’s profile and aggregating them for scale & reach.

Instead of one-size-fits-all services, the platform offers financial and non-financial products tailored to the specific occupations or needs of the community. This addresses the gap in current models where many products don’t fit the unique cash flows or risks of low-income livelihoods.

This model lends itself to inherent bundling of products & services thereby guaranteeing higher adoption and sustained usage. For example, a group of garment factory workers might struggle with long hours & low wages, require affordable housing, and have aspirations to start a small garment business, etc.

II. Suppliers can configure Products by ‘Livelihoods’

Banks, NBFCs, and other product manufacturers can plug in their offerings via APIs and configure them for niche segments. For example, a bank could offer a zero-balance salary account product designed for daily-wage workers (with weekly payout options), affordable vehicle loans for gig workers and tool/equipment loans for tailors or carpenters.

By collaborating with providers, the platform ensures products have flexible terms, low entry barriers and are highly relevant & valuable to the target users. Such customisation can increase product uptake and margins for parties involved.

By plugging into the marketplace, providers gain access to pre-aggregated user segments, community behaviour and data that can enable tailored marketing and underwriting to that segment’s risk profile.

III. Community Champions are set-up to monetize reach

Community Champions are individual influencers or micro-entrepreneurs from the same or similar community and/or livelihood. They are early adopters of products, act as role models and advocate for their livelihood.

They are not bound by geography: They can act as virtual BCs, building visibility, engagement and influence, online. Great examples are micro-influencers from the gig worker community like @BroCab99 or @Vamsidailytraveller619 or who have ~6K-60K followers.

AI helpers multiply their reach: Local language voice bots could handle routine balance checks or form-filling and hand off trickier questions to a human guide in seconds. This “bot-first, human-on-call” layer keeps support costs low while still offering the empathy users demand.

Their incentives scale with impact: The exchange could pay higher commissions for deeper engagement. Incentives could also be linked to outcomes for example increase in a household’s savings. Champions can also earn influencer income by creating content that links directly to the platform’s product pages. Micro-influencers in India average ₹5K–₹50K per sponsored post19

Plugging this model into large gig-platforms (Swiggy, Ola, Uber) can be straightforward; however structural elements of the platform should be preserved. Selected workers become champions while the rest join their groups; the exchange curates packages, everyone shops these livelihood bundles while the champion’s earnings grow with each active, satisfied user; and the gig platform takes a cut.

Operating Model

Traditional phygital networks have scaled breadth-wise – they aimed to plant agents in as many locations as possible to serve the masses. The Exchange scales through depth within targeted communities. Over the long term, the community model can still achieve scale by replicating across many communities – cluster-by-cluster rather than blanket presence.

Existing BC models incur prohibitive costs of hiring, training & retaining agents, acquiring customers for newer products, monitoring the network for compliance and running on-ground operations. This model aims to slash these costs with:

Network effects: Each new user in a group makes it slightly easier to get the next user (due to peer influence and shared trust), which could lower acquisition cost over time

Use of AI agents: The advantages extend from scaling at low cost, to 24/7 availability, consistency in responses to simple queries and multilingual/localised interactions (with voice tech)

Use of platform intelligence to monitor & mitigate fraud: With all data and transactions flowing through the platform, users can be monitored for fraud and compliance breaches in real-time

This model also explores newer opportunities for platform monetization:

The platform can charge the providers (supply) for successful product disbursals

The platform can charge a SaaS fee for banks to customize products

The model can unlock cross-subsidization for example, a corporate or NGO might pay to reach these communities for non-financial services (advertising a skilling program, for instance)

Challenges and Pitfalls

Building a community-driven livelihood exchange can unlock the ₹ 1 trillion20 cash economy of India’s urban underserved, but execution hurdles are formidable. Three choke points dominate: (1) Recruiting, retaining and motivating local community “champions”; (2) Aggregating demand from fragmented, mobile livelihood groups; (3) Convincing financial-service and non-financial providers to customize low-ticket products and still earn a margin. These are layered on top of operational, regulatory, and trust issues that plague existing phygital BC networks.

Mitigation strategies would involve first designing a small-scale proof of concept before expansion:

Identify dense, semi-organised groups of livelihoods to start off with

Identify groups that already have semi-formal community leaders embedded

Introduce attractive and sustainable incentives for community champions to generate a steady flow of demand

Curate the first set of simple yet attractive livelihood packages with just a couple of partners

After building data on the platform, venture into financial products backed with robust proxies for credit worthiness and demonstrated inclination to adopt bundled products.

In the long run, I see India’s future last-mile system as less of an either-or choice but more a tag-team: existing phygital BC agents keep every village/town on the grid, while a community-led “livelihood exchange” dives deep wherever it sets up. So the same locality might see a PayNearby agent handle cash-outs at one counter while a champion like Prakash guides co-workers to specialised credit next door.

The Livelihood Exchange model ensures that the platform isn’t just a static menu of products, but a living, breathing ecosystem: Users like Chennai’s factory workers are organized and empowered, Providers like banks compete and tailor their solutions, and Community Champions like Prakash grease the wheels by facilitating information flow and trust. The value proposition is that everyone wins – communities from the margins get access to relevant, high-quality solutions with guidance; providers reach underserved markets efficiently; and champions earn income and social capital by improving their community’s welfare.

Names of Ajit & Prakash have been changed to protect anonymity.

Using the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS 2022-23) distribution of urban principal earners by industry and re-weighting it with PRICE-ICE 360°’s income-band data we obtain the livelihood mix

INR 20 trillion arrived at by multiplying 405 M population (90M urban underserved HHs * 4.5) by 4000 (50th percentile of monthly per capita urban income) times 12. Assuming the exchange channels 5% of it, it becomes INR 1 trillion.

Fantastic story telling. The patchy distribution of core services reaching urban migrant workers is something that is seen the world over. Informal communities based on "hometown" networks have traditionally fill the gap somewhat but these have their pitfalls and limitations. Love your idea on community livelihood exchange as a much needed evolved model of this!!